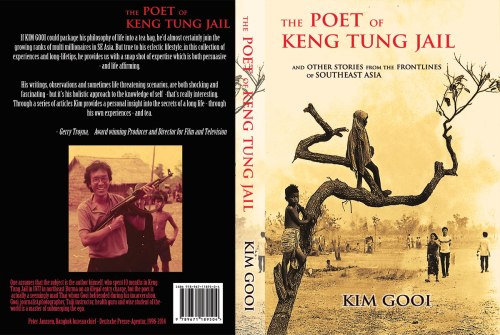

On page 3I8 of my book “The Poet of Keng Tung Jail” you can read and see some exclusive stuff about the Tunku

Epilogue

After my release and deportation from Burma, I went to see the Tunku to pass him the message from the Muslim leader in Insein Jail. The leader wanted the world to know about the atrocities and downright racism unleashed against the Rohingas by the Burmese military junta.

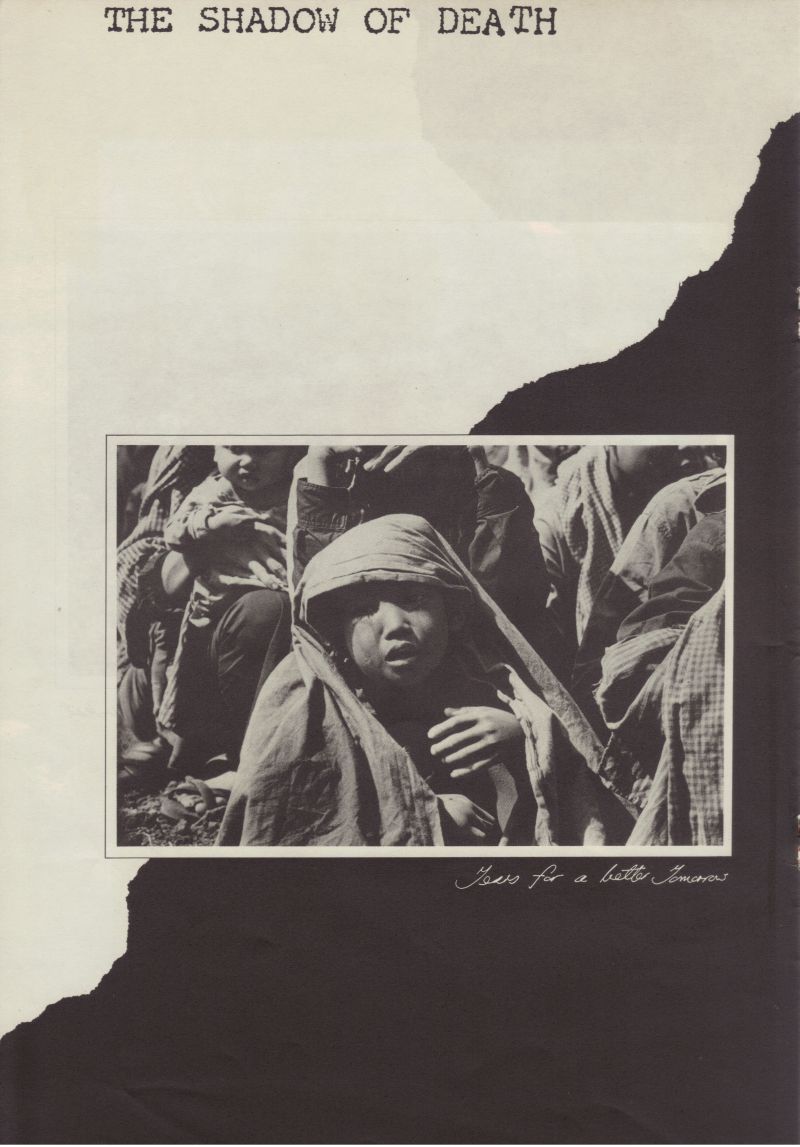

In one summer in 1978, 200,000 Rohingas from Arakan State fled across the border into Bangladesh to escape looting, killings and rape by the Burmese army.

Today, thirty-five years later, the situation had unbelievably worsened – with Buddhist monks instigating the attacks in what Burmese scholar, Maung Zarni, writing in his daily blog termed ’Burmese Buddhist Nazism and genocide’ against the Muslim minority.

Unlike the other chapters which were published in various magazines and newspapers, this has never been published before.

Many would vote Tunku Abdul Rahman as Malaysia’s most beloved prime minister because of his endearing ways. His wit, sharpness of mind, empathy and compassion for the common people were legendary.

But many of his admirers may not be aware of his colourful early career and his enduring connection with Thailand’s Muslim minority.

Much has been written about his political development and achievements. Robert McNamara, then-president of the World Bank, said in his opening address at the first Tun Abdul Razak Memorial lecture that he was envious of the Malaysians in the audience who had walked with the founding father of the nation, whereas he had to get to know the Tunku through the history books.

I was 10 years old in 1957 when the Tunku proclaimed independence from Britain and became the country’s first prime minister. I had the good fortune of meeting him several times in his later years. Watching him in action, listening to his wise words, I became one of his many admiring fans.

I first came face-to-face with the Tunku at his residence in Ayer Raja Road, Penang, in May 1978. He had long retired and hadnchosen Penang as his retirement home.

Why had he chosen Penang and not Kuala Lumpur? The people of Penang were honoured and happy that such a great man had chosen the island as his home. It was evident that he loved the island just as the islanders loved him.

It was about 10 in the morning. We were all waiting for the Tunku in the reception room cum office, staked with expensive souvenirs, trophies, walking sticks and memorabilia.

In a corner his Chinese secretary was pounding on a typewriter. Samad the driver and Owen Chung his ADC stood around chatting. I was seated beside a humble Malay lad of about 18. Facing us were three distinguished-looking men – two Chinese and an Indian Muslim. Obviously some rich tycoons, I thought.

As the Tunku came down the winding staircase, before I could stand up, the three big-shots went forward and greeted the old man with gusto. “Tunku Tunku! I just bought a 300-dollar shirt from Hong Kong for you. Can you play golf this Thursday? We’ve booked the golf course,” one of the Chinese said loudly.

Tunku, with hardly a glance, waved him aside. The second Chinese man cheerfully came forward and said, “Tunku, we’ve formed a Bumiputra company – 51 percent Malay and 49 percent Chinese. Can you sign for us? We got a piece of land in Balik Pulau, we want to develop into a holiday resort.”

Tunku retorted, “Where did the Malays get the money to form the company to do big business?”

The tycoon confessed, “Actually we put up the money for them.”

“I know the Malays have no money. You Chinese have the money but still I just can’t simply sign the application for you. You have to tell me who are these people, what is their background?” Tunku admonished.

“OK, OK! I’ll do that Tunku,” the guy said and quietly sat down. Then the Indian Muslim man happily announced that he had convinced a friend in Sungei Pattani to accept Islam.

Tunku nodded happily and asked him to sit down. He then came straight to the Malay lad and me and warmly shook our hands and attended to us, enquiring whether we had our coffee and how he could help us.

We said yes and thanked him for the coffee. The Malay boy and I felt 10 feet tall the way Tunku treated us in front of the three rich and powerful guests.

The Malay boy said he had left school after form three and could not find a job and his family were poor. Tunku told him if he was not fussy about manual work, he would get him a job with the JKR (Public Works Department) tending trees and parks, and promptly dictated a letter to the secretary.

Turning to me, he said, “You have a problem with your passport after deportation from Burma. Just yesterday the immigration director from KL was here to visit me. What a coincidence! He told me if I need any help don’t hesitate to tell him. I will give you a letter. You go to KL immigration and see him. You will get your passport back in no time.”

Two weeks earlier I had my first encounter with the Tunku and had spent several hours talking about the Burmese Rohinga refugees, while he tape-recorded it with a mini-tape recorder (very rare to see in 1978).

I was deported from Burma after a year in that country’s notorious jails. My crime was entering the country without a visa as a journalist. I was asked by the Muslim leader in the jail to see the Tunku when I got out and tell him all about their problems and persecution under the Burmese. [See story in Islamic Herald]

I wrote to Perkim, the Islamic Welfare Association founded by Tunku, and told them my situation and asked to see the Tunku as requested by the Muslim leader who was in jail with me. The reply was prompt and to my surprise they requested permission to print my letter in the Islamic Herald. It was the beginning of my very fortunate and happy friendship with the Tunku.

My passport had been taken away by the government and I was told that I was under investigation because of the jail sentence. The passport could only be returned after I was cleared.

When? It could be years or never, I was told. I had two jobs waiting for me in Bangkok – with the Businese Times newspaper and as a reporter for the US news agency UPI at the 1978 Asian Games.

But without a passport I was unemployable. Tunku was my savior; as the former PM and father of the nation, he had the authority to clear my name. Without him, my career and future would have been greatly jeopardised.

After these episodes I had many more encounters with the Tunku, each of them memorable, educational and an insight to his wisdom and humanity.

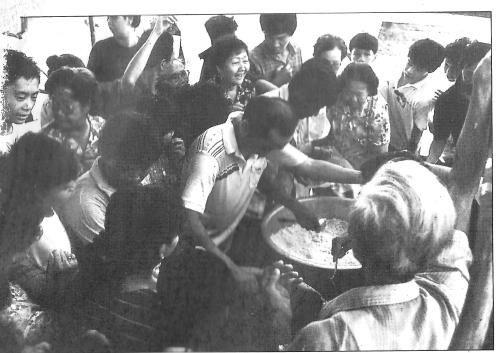

His birthday open houses were warm and touching affairs, with a generous spread of Malay food and other goodies. The Chinese families, around 60 per cent of those present, would surround him together with their little children, calling out: “Say happy birthday to Tunku!”

He loved children and the children swarmed around him naturally, taking to the kind old man like ducklings to water.

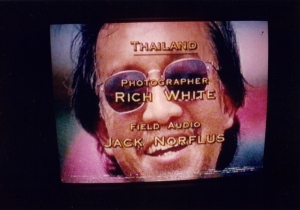

His visit to Bangkok in 1985 was another unforgettable event. By then my work had been going well and many of my articles were published in local and international media.

Tunku and his Perkim entourage came in Sarawak chief minister Taib Mahmud’s private jet. Taib was deputy president and Tunku’s right-hand man in Perkim. But there was no mention of the visit in the local press.

Tunku was very disappointed with Perkim’s press secretary (an Australian convert to Islam working for Perkim), said Tarmizi Hashim, the press attaché of the Malaysian embassy. Tarmizi rounded up the media. The next day the whole Bangkok press corp turned up to hear a beaming Tunku talk about Perkim’s important humanitarian work among Bangkok Muslims.

Tunku was a hit with the Thai reporters because he grew up in the Thai court of King Rama 6. To them, Tunku qualified as Thai royalty and the government honoured him with two police out-rider escorts whenever he comes to the kingdom.

He and his elder brother were “hostages” in the court as Kedah was still a vassal state of Siam at the turn of the century. He came back to Kedah in his early teens and studied at the Penang Free School. His elder brother stayed in Thailand and became a Major General in the Royal Thai Army.

“My brother died and was buried in a Bangkok Muslim cemetery,” the Tunku said. “When I became PM in 1957, the first thing I did was an official visit to Bangkok.”

“After being conferred the highest decoration, I went to the Muslim cemetery and exhumed my brother’s remains and brought them back to Kedah for reburial in my family’s cemetery. I am the only Muslim in the world who has done that,” Tunku said with a chuckle.

A Thai reporter asked Tunku whether he could still speak Thai. Tunku said that in Kedah, Thai spoken is differently from that spoken in Bangkok. Like “Tham Pleu, Tham Plue” means “What to do, what to do!

The next day it was front-page in all the dailies: “Tunku speaks fluent Thai,” together with the comment that Tunku also pointed out Malaysian journalist Kim Gooi who was jailed in Burma whom he knows.

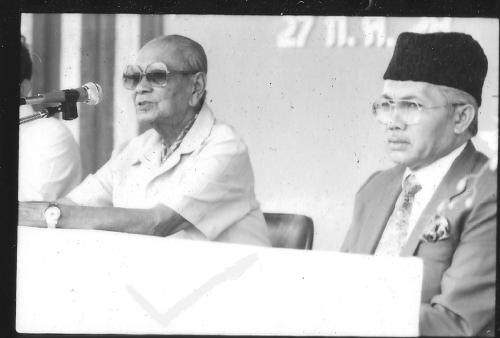

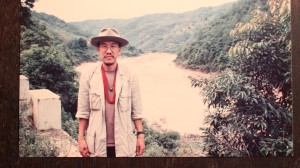

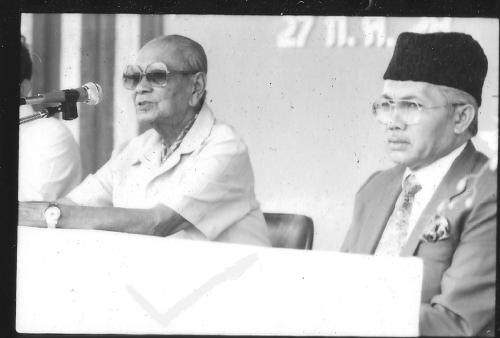

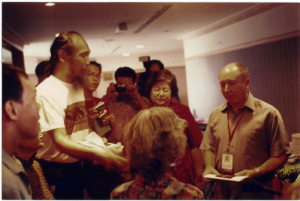

Bangkok, 27 Jul 1985: – Tunku, wearing hat on left, with the descendants of Kedahans in Nongchok, outskirt of Bangkok

The Tunku with the people of Nongchok, Bangkok 27 Jul 1985

The Tunku addressing the people of Nongchok, with him is Tan Sri Taib Mahmud

The Tunku pointed out that the residents of the big Muslim community of Nongchok on Bangkok’s outskirts were descendants of Kedah slaves captured and brought to Bangkok to build the canals in the last century. That’s why all the mosques and many Muslim community are along the canals.

These were his people captured as slaves and brought from Kedah to dig the canals. Tunku never forgets them, they were close to his heart. Thank God, they survived and living well as the land where many settled has become valuable now, he commented.

Tunku also remembered he complained to the Thai government during the official visit that there was no central mosque in Bangkok despite the substantial number of Muslims. The result was the big mosque we see today at Hua Mak district of Bangkok, he said proudly.

In December 1985 Malaysian press attaché Tamizi arranged a meeting for me to meet opium king Khun Sa at his stronghold on the Thai-Burmese border. (5-part-story printed in NST Jan 27-Jan 31,1986). The guide and escort was a Chinese Muslim ex-general of the Kuomintang Army, Ma Sian.

Ma was an admirer of the Tunku and I suggested to him to present the Shan army commanders’ walking stick to Tunku. It is a beautiful rattan cane as thick as a toe with a curve handle. All the commanders carry one into battle and Khun Sa carried one whenever he inspected his troops.

The cane was duly delivered to the embassy. After a few months Tamizi told me that the embassy could not send it to Tunku because it is not proper coming from Khun Sa, the opium warlord of the Golden Triangle. You have to take it and deliver it to him yourself, they told me.

I presented the cane to him in 1987 and said it was from the Shan people. By coincidence I was told by Colonel Khern Sai of the Shan State Army that the Tunku’s mother was actually a Shan princess. This was not too surprising, considering that the Shan and Thai are branches of the same family of people.

As usual we had coffee and a long chat. When I told him I had been to the Philippines to cover the Aquino assassination, he told me of the arrogance and offences committed by then-president Ferdinand Marcos against our Agong (Malaysian King) a few years ago. Our Agong, after retirement went for a round-the-world cruise.

During a stopover in Manila, our ambassador arranged for a visit to Malacanyang Palace. When the Agong’s limousine arrived at the palace gate, Marcos ordered the car to stop and the Agong had to walk up the driveway to the palace. Our ambassador was aghast and protested. Finally Marcos relented and a great insult to Malaysia was averted.

“Even then Marcos showed his arrogance,” said Tunku. “Instead of coming to the door to greet our Agong. He stood behind the desk and made the Agong walked up to greet him.

“This was too much,” Tunku said indignantly.

In 1986, Marcos had to flee the Philippines and died in exile in Hawaii three years later.

For a journalist, talking to the Tunku was a goldmine of information. I was privy to many exclusive bits of information.

On one occasion the Tunku asked me how I had come to his house and how I planned to return to Tanjung Bungah. I told him I took a taxi and intended to walk to Pulau Tikus and take a bus back.

He said he could give me a lift to Pulau Tikus since he went there most afternoons, to his favorite market to shop around.

In the car, his bodyguard Owen Chung was in the front beside Samad. I sat proudly in the back sitting beside the Tunku as the limousine eased out of the driveway and cruised along the tree-lined Ayer Raja Road, to Cantonment Road towards Pulau Tikus. That was the most memorable ride ever in my life.

The stories and photographs compiled here had been published in various regional newspapers and magazines during my career as a freelance journalist, beginning from the mid seventies onwards. Except for one – Waiting for the Tunku – which for various reasons had never been written until now.

The stories and photographs compiled here had been published in various regional newspapers and magazines during my career as a freelance journalist, beginning from the mid seventies onwards. Except for one – Waiting for the Tunku – which for various reasons had never been written until now.

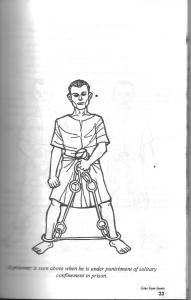

For example, if I were to tell you that the lines of poetry above were taken from a journalistic memoir I wrote called “The Poet of Keng Tung Jail”, you might assume that I had arranged to visit the jail on assignment. However, I was not a visiting journalist. I was myself a prisoner in Keng Tung. Who, then, is the “Poet?” Me, perhaps? But the lines are not mine. They are an excerpt from a poem called “January”, written by a Thai prisoner called Taworn.

For example, if I were to tell you that the lines of poetry above were taken from a journalistic memoir I wrote called “The Poet of Keng Tung Jail”, you might assume that I had arranged to visit the jail on assignment. However, I was not a visiting journalist. I was myself a prisoner in Keng Tung. Who, then, is the “Poet?” Me, perhaps? But the lines are not mine. They are an excerpt from a poem called “January”, written by a Thai prisoner called Taworn.

[1st published in Dateline Bangkok, 1st quarter 1984; 2nd publication in the Bangkok World, Tuesday October 23, 1984]

[1st published in Dateline Bangkok, 1st quarter 1984; 2nd publication in the Bangkok World, Tuesday October 23, 1984]

Cheah Siew Chee, 80

Cheah Siew Chee, 80 Ameena Amnal, 70

Ameena Amnal, 70 Champion of the urban poor, Ong Boon Keong, with the inner city’s residents facing eviction, handing a petition to Unesco’s Richard Engelhardt – George Town, 21 April 2002

Champion of the urban poor, Ong Boon Keong, with the inner city’s residents facing eviction, handing a petition to Unesco’s Richard Engelhardt – George Town, 21 April 2002